NEET MDS Lessons

Orthodontics

Growth is the increase in size It may also be defined as the normal change in the amount of living substance. eg. Growth is the quantitative aspect and measures in units of increase per unit of time.

Development

It is the progress towards maturity (Todd). Development may be defined as natural sequential series of events between fertilization of ovum and adult stage.

Maturation

It is a period of stabilization brought by growth and development.

CEPHALOCAUDAL GRADIENT OF GROWTH

This simply means that there is an axis of increased growth extending from the head towards feet. At about 3rd month of intrauterine life the head takes up about 50% of total body length. At this stage cranium is larger relative to face. In contrast the limbs are underdeveloped.

By the time of birth limbs and trunk have grown faster than head and the entire proportion of the body to the head has increased. These processes of growth continue till adult.

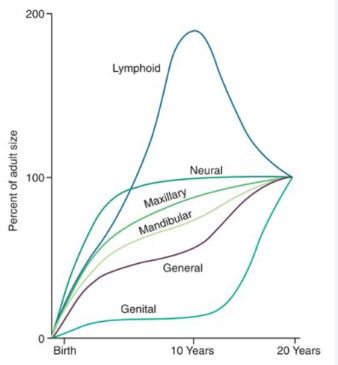

SCAMMON’S CURVE

In normal growth pattern all the tissue system of the body do not growth at the same rate. Scammon’s curve for growth shows 4 major tissue system of the body;

• Neural

• Lymphoid

• General: Bone, viscera, muscle.

• Genital

The graph indicates the growth of the neural tissue is complete by 6-7 year of age. General body tissue show an “S” shaped curve with showing of rate during childhood and acceleration at puberty. Lymphoid tissues proliferate to its maximum in late childhood and undergo involution. At the same time growth of the genital tissue accelerate rapidly.

Thumb Sucking

According to Gellin, thumb sucking is defined as “the placement of the thumb or one or more fingers in varying depth into the mouth.” This behavior is common in infants and young children, serving as a self-soothing mechanism. However, prolonged thumb sucking can lead to various dental and orthodontic issues.

Diagnosis of Thumb Sucking

1. History

- Psychological Component: Assess any underlying psychological factors that may contribute to the habit, such as anxiety or stress.

- Frequency, Intensity, and Duration: Gather information on how often the child engages in thumb sucking, how intense the habit is, and how long it has been occurring.

- Feeding Patterns: Inquire about the child’s feeding habits, including breastfeeding or bottle-feeding, as these can influence thumb sucking behavior.

- Parental Care: Evaluate the parenting style and care provided to the child, as this can impact the development of habits.

- Other Habits: Assess for the presence of other oral habits, such as pacifier use or nail-biting, which may coexist with thumb sucking.

2. Extraoral Examination

- Digits:

- Appearance: The fingers may appear reddened, exceptionally clean, chapped, or exhibit short fingernails (often referred to as "dishpan thumb").

- Calluses: Fibrous, roughened calluses may be present on the superior aspect of the finger.

- Lips:

- Upper Lip: May appear short and hypotonic (reduced muscle tone).

- Lower Lip: Often hyperactive, showing increased movement or tension.

- Facial Form Analysis:

- Mandibular Retrusion: Check for any signs of the lower jaw being positioned further back than normal.

- Maxillary Protrusion: Assess for any forward positioning of the upper jaw.

- High Mandibular Plane Angle: Evaluate the angle of the mandible, which may be increased due to the habit.

3. Intraoral Examination

-

Clinical Features:

- Intraoral:

- Labial Flaring: Maxillary anterior teeth may show labial flaring due to the pressure from thumb sucking.

- Lingual Collapse: Mandibular anterior teeth may exhibit lingual collapse.

- Increased Overjet: The distance between the upper and lower incisors may be increased.

- Hypotonic Upper Lip: The upper lip may show reduced muscle tone.

- Hyperactive Lower Lip: The lower lip may be more active, compensating for the upper lip.

- Tongue Position: The tongue may be placed inferiorly, leading to a posterior crossbite due to maxillary arch contraction.

- High Palatal Vault: The shape of the palate may be altered, resulting in a high palatal vault.

- Intraoral:

-

Extraoral:

- Fungal Infection: There may be signs of fungal infection on the thumb due to prolonged moisture exposure.

- Thumb Nail Appearance: The thumb nail may exhibit a dishpan appearance, indicating frequent moisture exposure and potential damage.

Management of Thumb Sucking

1. Reminder Therapy

- Description: This involves using reminders to help the child become aware of their thumb sucking habit. Parents and caregivers can gently remind the child to stop when they notice them sucking their thumb. Positive reinforcement for not engaging in the habit can also be effective.

2. Mechanotherapy

- Description: This approach involves using mechanical

devices or appliances to discourage thumb sucking. Some options include:

- Thumb Guards: These are devices that fit over the thumb to prevent sucking.

- Palatal Crib: A fixed appliance that can be placed in the mouth to make thumb sucking uncomfortable or difficult.

- Behavioral Appliances: Appliances that create discomfort when the child attempts to suck their thumb, thereby discouraging the habit.

Lip habits refer to various behaviors involving the lips that can affect oral health, facial aesthetics, and dental alignment. These habits can include lip biting, lip sucking, lip licking, and lip pursing. While some lip habits may be benign, others can lead to dental and orthodontic issues if they persist over time.

Common Types of Lip Habits

-

Lip Biting:

- Description: Involves the habitual biting of the lips, which can lead to chapped, sore, or damaged lips.

- Causes: Often associated with stress, anxiety, or nervousness. It can also be a response to boredom or concentration.

-

Lip Sucking:

- Description: The act of sucking on the lips, similar to thumb sucking, which can lead to changes in dental alignment.

- Causes: Often seen in young children as a self-soothing mechanism. It can also occur in response to anxiety or stress.

-

Lip Licking:

- Description: Habitual licking of the lips, which can lead to dryness and irritation.

- Causes: Often a response to dry lips or a habit formed during stressful situations.

-

Lip Pursing:

- Description: The act of tightly pressing the lips together, which can lead to muscle tension and discomfort.

- Causes: Often associated with anxiety or concentration.

Etiology of Lip Habits

- Psychological Factors: Many lip habits are linked to emotional states such as stress, anxiety, or boredom. Children may develop these habits as coping mechanisms.

- Oral Environment: Factors such as dry lips, dental issues, or malocclusion can contribute to the development of lip habits.

- Developmental Factors: Young children may engage in lip habits as part of their exploration of their bodies and the world around them.

Clinical Features

-

Dental Effects:

- Malocclusion: Prolonged lip habits can lead to changes in dental alignment, including open bites, overbites, or other malocclusions.

- Tooth Wear: Lip biting can lead to wear on the incisal edges of the teeth.

- Gum Recession: Chronic lip habits may contribute to gum recession or irritation.

-

Soft Tissue Changes:

- Chapped or Cracked Lips: Frequent lip licking or biting can lead to dry, chapped, or cracked lips.

- Calluses: In some cases, calluses may develop on the lips due to repeated biting or sucking.

-

Facial Aesthetics:

- Changes in Lip Shape: Prolonged habits can lead to changes in the shape and appearance of the lips.

- Facial Muscle Tension: Lip habits may contribute to muscle tension in the face, leading to discomfort or changes in facial expression.

Management

-

Behavioral Modification:

- Awareness Training: Educating the individual about their lip habits and encouraging them to become aware of when they occur.

- Positive Reinforcement: Encouraging the individual to replace the habit with a more positive behavior, such as using lip balm for dry lips.

-

Psychological Support:

- Counseling: For individuals whose lip habits are linked to anxiety or stress, counseling or therapy may be beneficial.

- Relaxation Techniques: Teaching relaxation techniques to help manage stress and reduce the urge to engage in lip habits.

-

Oral Appliances:

- In some cases, orthodontic appliances may be used to discourage lip habits, particularly if they are leading to malocclusion or other dental issues.

-

Dental Care:

- Regular Check-Ups: Regular dental visits can help monitor the effects of lip habits on oral health and provide guidance on management.

- Treatment of Dental Issues: Addressing any underlying dental problems, such as cavities or misalignment, can help reduce the urge to engage in lip habits.

Wayne A. Bolton Analysis

Wayne A. Bolton's analysis, which is a critical tool in orthodontics for assessing the relationship between the sizes of maxillary and mandibular teeth. This analysis aids in making informed decisions regarding tooth extractions and achieving optimal dental alignment.

Key Concepts

Importance of Bolton's Analysis

- Tooth Material Ratio: Bolton emphasized that the extraction of one or more teeth should be based on the ratio of tooth material between the maxillary and mandibular arches.

- Goals: The primary objectives of this analysis are to achieve ideal interdigitation, overjet, overbite, and overall alignment of teeth, thereby attaining an optimum interarch relationship.

- Disproportion Assessment: Bolton's analysis helps identify any disproportion between the sizes of maxillary and mandibular teeth.

Procedure for Analysis

To conduct Bolton's analysis, the following steps are taken:

-

Measure Mesiodistal Diameters:

- Calculate the sum of the mesiodistal diameters of the 12 maxillary teeth.

- Calculate the sum of the mesiodistal diameters of the 12 mandibular teeth.

- Similarly, calculate the sum for the 6 maxillary anterior teeth and the 6 mandibular anterior teeth.

-

Overall Ratio Calculation: [ \text{Overall Ratio} = \left( \frac{\text{Sum of mesiodistal width of mandibular 12 teeth}}{\text{Sum of mesiodistal width of maxillary 12 teeth}} \right) \times 100 ]

- Mean Value: 91.3%

-

Anterior Ratio Calculation: [ \text{Anterior Ratio} = \left( \frac{\text{Sum of mesiodistal width of mandibular 6 teeth}}{\text{Sum of mesiodistal width of maxillary 6 teeth}} \right) \times 100 ]

- Mean Value: 77.2%

Inferences from the Analysis

The results of Bolton's analysis can lead to several important inferences regarding treatment options:

-

Excessive Mandibular Tooth Material:

- If the ratio is greater than the mean value, it indicates that the mandibular tooth material is excessive.

-

Excessive Maxillary Tooth Material:

- If the ratio is less than the mean value, it suggests that the maxillary tooth material is excessive.

-

Treatment Recommendations:

- Proximal Stripping: If the upper anterior tooth material is in excess, Bolton recommends performing proximal stripping on the upper arch.

- Extraction of Lower Incisors: If necessary, extraction of lower incisors may be indicated to reduce tooth material in the lower arch.

Drawbacks of Bolton's Analysis

While Bolton's analysis is a valuable tool, it does have some limitations:

-

Population Specificity: The study was conducted on a specific population, and the ratios obtained may not be applicable to other population groups. This raises concerns about the generalizability of the findings.

-

Sexual Dimorphism: The analysis does not account for sexual dimorphism in the width of maxillary canines, which can lead to inaccuracies in certain cases.

Myofunctional Appliances

- Myofunctional appliances are removable or fixed devices that aim to correct dental and skeletal discrepancies by promoting proper oral and facial muscle function. They are based on the principles of myofunctional therapy, which focuses on the relationship between muscle function and dental alignment.

-

Mechanism of Action:

- These appliances work by encouraging the correct positioning of the tongue, lips, and cheeks, which can help guide the growth of the jaws and the alignment of the teeth. They can also help in retraining oral muscle habits that may contribute to malocclusion, such as thumb sucking or mouth breathing.

Types of Myofunctional Appliances

-

Functional Appliances:

- Bionator: A removable appliance that encourages forward positioning of the mandible and helps in correcting Class II malocclusions.

- Frankel Appliance: A removable appliance that modifies the position of the dental arches and improves facial aesthetics by influencing muscle function.

- Activator: A functional appliance that promotes mandibular growth and corrects dental relationships by positioning the mandible forward.

-

Tongue Retainers:

- Devices designed to maintain the tongue in a specific position, often used to correct tongue thrusting habits that can lead to malocclusion.

-

Mouthguards:

- While primarily used for protection during sports, certain types of mouthguards can also be designed to promote proper tongue posture and prevent harmful oral habits.

-

Myobrace:

- A specific type of myofunctional appliance that is used to correct dental alignment and improve oral function by encouraging proper tongue posture and lip closure.

Indications for Use

- Malocclusions: Myofunctional appliances are often indicated for treating Class II and Class III malocclusions, as well as other dental alignment issues.

- Oral Habits: They can help in correcting harmful oral habits such as thumb sucking, tongue thrusting, and mouth breathing.

- Facial Growth Modification: These appliances can be used to influence the growth of the jaws in growing children, promoting a more favorable dental and facial relationship.

- Improving Oral Function: They can enhance functions such as chewing, swallowing, and speech by promoting proper muscle coordination.

Advantages of Myofunctional Appliances

- Non-Invasive: Myofunctional appliances are generally non-invasive and can be a more comfortable option for patients compared to fixed appliances.

- Promotes Natural Growth: They can guide the natural growth of the jaws and teeth, making them particularly effective in growing children.

- Improves Oral Function: By retraining oral muscle function, these appliances can enhance overall oral health and function.

- Aesthetic Appeal: Many myofunctional appliances are less noticeable than traditional braces, which can be more appealing to patients.

Limitations of Myofunctional Appliances

- Compliance Dependent: The effectiveness of myofunctional appliances relies heavily on patient compliance. Patients must wear the appliance as prescribed for optimal results.

- Limited Scope: While effective for certain types of malocclusions, myofunctional appliances may not be suitable for all cases, particularly those requiring significant tooth movement or surgical intervention.

- Adjustment Period: Patients may experience discomfort or difficulty adjusting to the appliance initially, which can affect compliance.

Lip Bumper

A lip bumper is an orthodontic appliance designed to create space in the dental arch by preventing the lips from exerting pressure on the teeth. It is primarily used in growing children and adolescents to manage dental arch development, particularly in cases of crowding or to facilitate the eruption of permanent teeth. The appliance is typically used in the lower arch but can also be adapted for the upper arch.

Indications for Use

-

Crowding:

- To create space in the dental arch for the proper alignment of teeth, especially when there is insufficient space for the eruption of permanent teeth.

-

Anterior Crossbite:

- To help correct anterior crossbites by allowing the anterior teeth to move into a more favorable position.

-

Eruption Guidance:

- To guide the eruption of permanent molars and prevent them from drifting mesially, which can lead to malocclusion.

-

Preventing Lip Pressure:

- To reduce the pressure exerted by the lips on the anterior teeth, which can contribute to dental crowding and misalignment.

-

Space Maintenance:

- To maintain space in the dental arch after the premature loss of primary teeth.

Design and Features

-

Components:

- The lip bumper consists of a wire framework that is typically made

of stainless steel or other durable materials. It includes:

- Buccal Tubes: These are attached to the molars to anchor the appliance in place.

- Arch Wire: A flexible wire that runs along the buccal side of the teeth, providing the necessary space and support.

- Lip Pad: A soft pad that rests against the lips, preventing them from exerting pressure on the teeth.

- The lip bumper consists of a wire framework that is typically made

of stainless steel or other durable materials. It includes:

-

Customization:

- The appliance is custom-fitted to the patient’s dental arch to ensure comfort and effectiveness. Adjustments can be made to accommodate changes in the dental arch as treatment progresses.

Mechanism of Action

-

Space Creation:

- The lip bumper creates space in the dental arch by pushing the anterior teeth backward and allowing the posterior teeth to erupt properly. The lip pad prevents the lips from applying pressure on the anterior teeth, which can help maintain the space created.

-

Guiding Eruption:

- By maintaining the position of the molars and preventing mesial drift, the lip bumper helps guide the eruption of the permanent molars into their proper positions.

-

Facilitating Growth:

- The appliance can also promote the growth of the dental arch, allowing for better alignment of the teeth as they erupt.

Steiner's Analysis

Steiner's analysis is a widely recognized cephalometric method used in orthodontics to evaluate the relationships between the skeletal and dental structures of the face. Developed by Dr. Charles A. Steiner in the 1950s, this analysis provides a systematic approach to assess craniofacial morphology and is particularly useful for treatment planning and evaluating the effects of orthodontic treatment.

Key Features of Steiner's Analysis

-

Reference Planes and Points:

- Sella (S): The midpoint of the sella turcica, a bony structure in the skull.

- Nasion (N): The junction of the frontal and nasal bones.

- A Point (A): The deepest point on the maxillary arch between the anterior nasal spine and the maxillary alveolar process.

- B Point (B): The deepest point on the mandibular arch between the anterior nasal spine and the mandibular alveolar process.

- Menton (Me): The lowest point on the symphysis of the mandible.

- Gnathion (Gn): The midpoint between Menton and Pogonion (the most anterior point on the chin).

- Pogonion (Pog): The most anterior point on the contour of the chin.

-

Reference Lines:

- SN Plane: A line drawn from Sella to Nasion, representing the cranial base.

- ANB Angle: The angle formed between the lines connecting A Point to Nasion and B Point to Nasion. It indicates the relationship between the maxilla and mandible.

- Facial Plane (FP): A line drawn from Gonion (Go) to Menton (Me), used to assess the facial profile.

-

Key Measurements:

- ANB Angle: Indicates the anteroposterior

relationship between the maxilla and mandible.

- Normal Range: Typically between 2° and 4°.

- SN-MP Angle: The angle between the SN plane and the

mandibular plane (MP), which helps assess the vertical position of the

mandible.

- Normal Range: Usually between 32° and 38°.

- Wits Appraisal: The distance between the perpendiculars dropped from points A and B to the occlusal plane. It provides insight into the anteroposterior relationship of the dental bases.

- ANB Angle: Indicates the anteroposterior

relationship between the maxilla and mandible.

Clinical Relevance

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning: Steiner's analysis helps orthodontists diagnose skeletal discrepancies and plan appropriate treatment strategies. It provides a clear understanding of the patient's craniofacial relationships, which is essential for effective orthodontic intervention.

- Monitoring Treatment Progress: By comparing pre-treatment and post-treatment cephalometric measurements, orthodontists can evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment and make necessary adjustments.

- Predicting Treatment Outcomes: The analysis aids in predicting the outcomes of orthodontic treatment by assessing the initial skeletal and dental relationships.